Show all articles

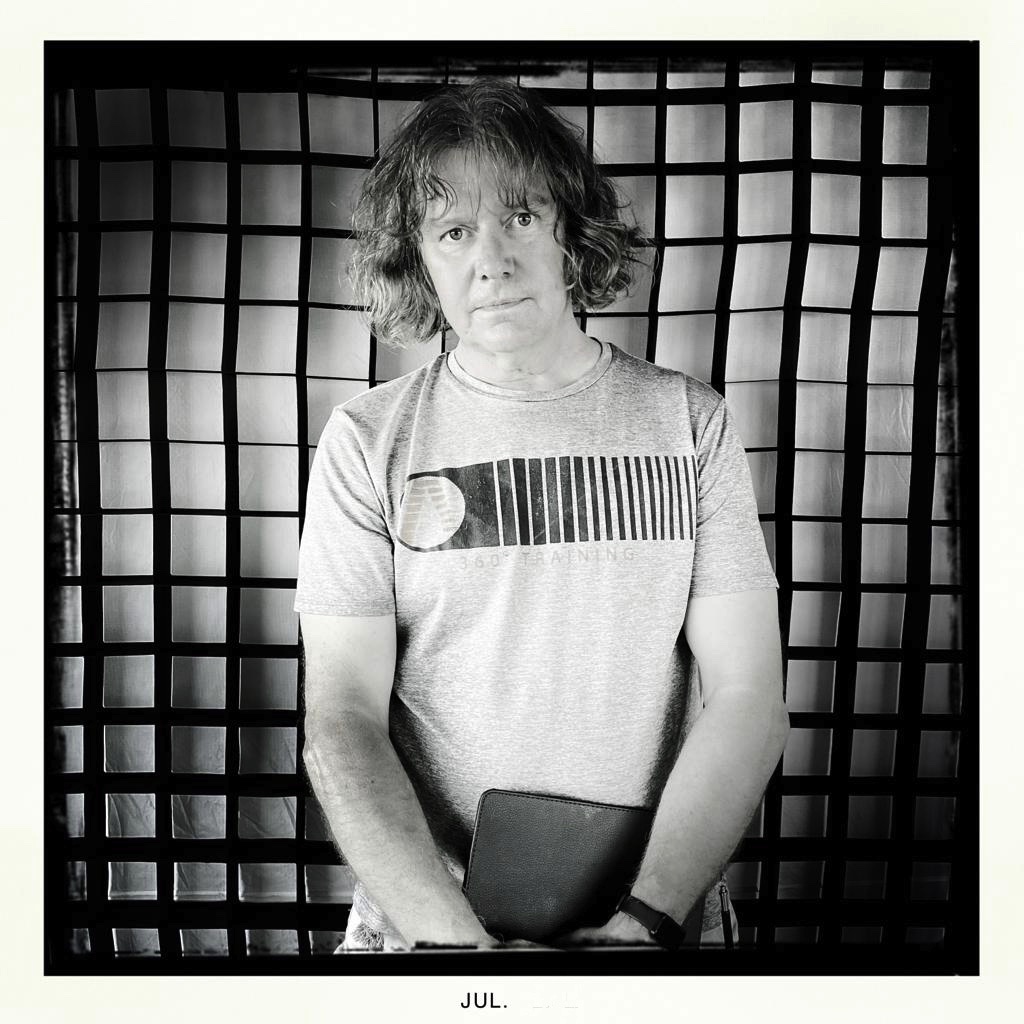

Piotr Kukla - No plans on retiring any time soon!

Amsterdam, 2023-01-06 - Gerlinda Heywegen

Fantastic. Piotr Kukla will often use that word in this interview when he is talking about something or someone. A little afraid that he won’t be able to work in the Netherlands anymore because of his age, enthusiastic about his students at the Łódź Film School in Poland. Full of love for the directors he has worked with for years, and where storyboarding is sacred.

A conversation with Kukla round the corner from where he lives, in a café in The Hague in November 2022.

Without waiting for the first question, Piotr Kukla (Bydgoszcz, Poland, 1958) starts talking about when he started in the Netherlands. It took a long time, he says, before he started getting anywhere. He talks about his terrific early days at the VPRO [Dutch public broadcaster, GH.] and refers to the NSC interview earlier this year with Sander Snoep. Kukla too felt that it was a ‘fantastic’ time. Everything was possible, directors like Pieter Kramer, Cherry Duyns, Rita Horst and Hans Keller could make films in complete freedom. And there were the same camera people for certain programmes. But it wasn’t easy, he explains, at length. “I’ve painted ceilings to earn money, and at a given moment, I thought, ‘This isn’t going to work.’”

Kukla studied cinema photography at the Łódź Film School, Poland, and explains that his father was a baker specialising in pastries and cakes, that he was the youngest of five children and that culture and showbiz was not an obvious career choice. His parents didn’t like it. Despite this, Kukla discovered early on what he wanted to be when just 14. He had seen a documentary on television about the cameraman Karol Szczecinski (1911 – 1995) and he immediately knew he wanted to do that as well. Szczecinski, explains Kukla, made films, mainly short ones, for almost 40 years. And he directed and acted as well. “I went to see so many films,” he says. He wasn’t accepted by the film school the first year, but he was lucky the following year. Of the 600 candidates who applied, only six were allowed to start and he was one of them. He had been given an 8mm camera by his father, had mainly filmed his family and taken lots of photos. That was enough.

“Everyone had more contacts in the film world than me. I loved it, I spent the whole day at the academy, I watched films constantly. French, Italian, the classics. I was having the time of my life, until a state of emergency was declared in 1981. Lech Walesa, you know the story. It was like a bad movie. My girlfriend was pregnant and managed to get to Paris by bribing people. My son was born there. The first time I saw him was on the big screen, in the cinema. He was a couple of months old. As an extra in Danton [Andrzej Wajda, 1983] with Gerard Depardieu. At a given moment in the story, a naked baby is held up high in a courtroom. Wajda was filming at that time in Paris, my girlfriend knew him and they were looking for a baby. I went, in Poland, with a friend to the Ivanovo Cinema in Łódź, a very big cinema, with a bottle of vodka and that’s when I saw my child for the first time.”

1989

A year later, Kukla also left Poland, following his family. He left everything behind. He needed a visa to stay in Paris and it so happened that he met some Dutch people, including Jan van Etten, then a journalist for De Haagsche Courant newspaper. “He turned out to be the most important man in my life.” Kukla leans in towards the recorder and says, “Jan, thank you”.

Van Etten decided to help Kukla come and stay in the Netherlands. “I had to report at the police station every Wednesday. I got to know people at the art cinema on Denneweg in The Hague, Kees Kasander, for example, and I met Peter Greenaway through him. I was able to work on The Cook, The Thief, His Wife and Her Lover as an electrician, but that was years later [1989, GH]. I also tried to get a visa for France to see my family, because it was so difficult to find work here.” He explains that he sometimes didn’t get work there either, with Agnieszka Holland, for instance. “I was going to work with her, but a day before I was supposed to start, it got cancelled by the French union. It wasn’t allowed, because I was Polish, not French.”

But after 1989, things got easier. Kukla received his Dutch passport in October 1989, the month the Wall fell. “I could finally start to develop. Until then I had done all sorts of odd jobs in Paris and the Netherlands, even walking dogs. I did anything, we were so poor.”

After waiting five years, once he had his Dutch passport, he soon worked with Pieter Kramer, starting as a lighting technician on Theo en Thea en de ontmaskering van het tenekaasimperium (1989). He shot his first feature film in The Hague, Rosa Rosa (Martin Uitvlugt, 1990), which he describes as ‘a little film’.

A few years later, his longstanding collaboration with Ben Sombogaart began with their first film together De jongen die niet meer praatte [The Boy Who Stopped Talking, 1996]. A major production, says Kukla, with a great script. He wanted to film the story about Memo, a Kurdish boy who has to move to the Netherlands with his mother and sister, because it isn’t safe in his own country and his father is already working there. Kukla names Sombogaart’s other films, De tweeling [Twin Sisters, 2002], Bride Flight (2008), De Storm [The Storm, 2009] and In My Father's Garden [Knielen op een bed violen, 2016].

UNDRESSING

What is striking in the conversation is that Kukla seems to regard his work as if he hadn’t filmed it himself. He thinks that In My Father's Garden is wonderful, reserving all his compliments for the actors, and Sombogaart. He likes to talk about the colouring in the film, which had to be so dark in many scenes. And: “I am really into storyboarding. I like to be fully prepared. Twenty days we went through the script. Ben’s assistants write down everything we say, we plan every scene. Twenty days of ‘undressing’. That’s how I build the scenes, that’s how I think about the colour. Ben loves to have an overview and we get it this way.”

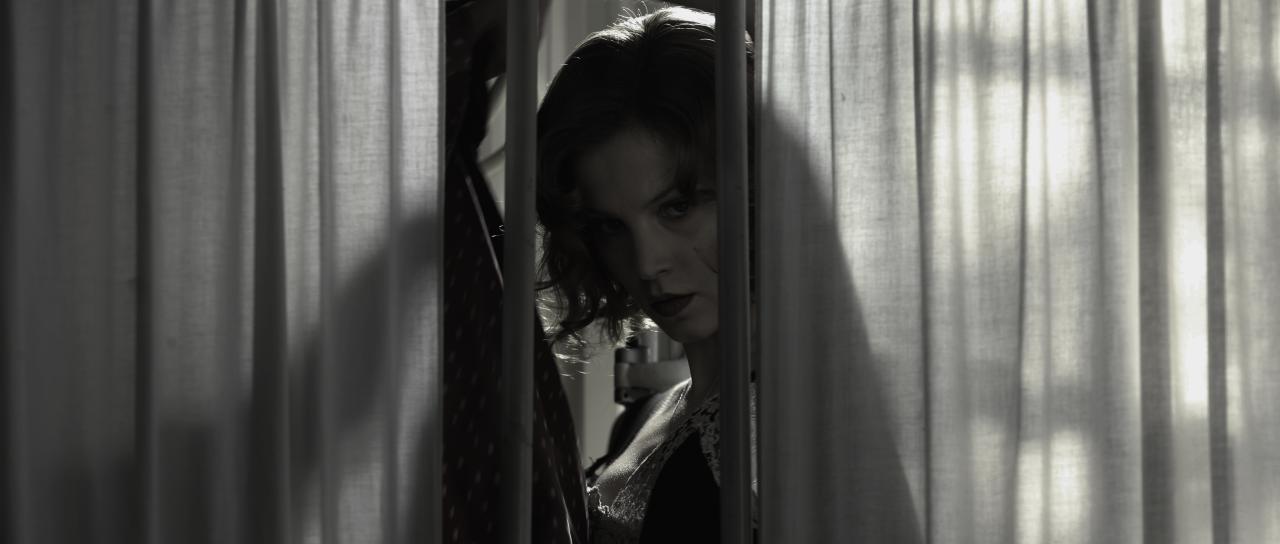

In Sombogaart’s version of Jan Siebelink’s book of the same name, the family of the commercial flower grower and main character Hans Sievez, played by Barry Atsma, begins to suffer more and more from his increasing fanaticism after he becomes more involved in a strict church community.

For the film, they did something that is quite unusual, and also, according to Kukla, difficult. Some scenes were ‘mocked up’ while still in pre-production, with the actors already in their costumes and Kukla working on how it all had to look. “So we could see what we wanted”, he says. “More colour, less colour. This way, I didn’t have to wait till the day of the shoot to see the result, with the risk that there might not be enough time to make any adjustment.”

He says that Barry Atsma’s character’s death scene was difficult. That small room, all those people dressed in black. It had to be oppressive, really oppressive, but not grotesque. Just darkness on its own wouldn’t have worked. Where do you put the colour and where do you put the light? “I think the beauty of the film is that there is that light at the beginning, there’s lots of colour, and then it all slowly disappears. I think that that worked really well. The flowers worked so well for that. It’s precisely because of them that I could put a lot of colour in at the start.

“With Twin Sisters as well, we completely prepared a test scene, I wanted to get the mise-en-scène right, and most important of all, I could try different colours that way, because the film gets two layers then. It was important to see if it worked, if it came over well.

Being a cameraman is about combining art and technical competence with each other. I don’t need to prove anything. I am inspired by a director, Sombogaart, in this case. Then I go with it. Everything happens in consultation, but I am at his service, absolutely. If we argue, it means that I’m not the right man for the job.

After Twin Sisters, I was pigeonholed: I was the DoP who made traditional films, but I’d made entirely different things before that. I’ve filmed Iggy Pop, Ice Cube, Ice-T and Loudon Wainwright III [for iconic music television show Lolapaloeza with director Bram van Splunteren, GH].” That is now classic television, and Kukla had often been there. “It’s just by chance that I went in this direction. As if I wouldn’t want to film anything else.”

SHOOTING WITH FILM

He does, and did, that ‘something else’ with the film-maker Wim van der Aar, for example. Kukla made a lot of documentaries with him, but they also made a lot of adverts together - you have to earn a living somehow. It allowed them to make their own films. Now that they are older, there is less commercial work. “But I had another job like that not so long ago", says Kukla, “and that makes me really happy, because then I can continue to do what I want, practise my hobby, make the films I want to make.” The fee for Zelazny most (Monika Jordan-Mlodzianowska, 2019), about which Kukla talks enthusiastically, was very low, he says. “I could shoot a commercial film in the Netherlands at the same time [Kukla prefers to keep the title to himself], but shooting the advert meant that I could go for Zelazny most, which I preferred.”

Kukla says that the film, about two men, one woman, somewhere in Poland in the mine industry, is fantastic. The story about a man who has an affair with the wife of another, his friend and colleague, and sends him away into the mines with all its consequences, is constantly referred to in the conversation. “I’m also going to be shooting Monika’s new film next year,” says Kukla, almost proudly. The film will be on Netflix.

He is also working again with Wim van der Aar on a documentary about Dutch people who have got lost somewhere on the way to Scotland from the Netherlands. “We are shooting with film. I enjoy that even more. You stand there, no monitor, me, Wim, the sound man, nothing else. Wonderful. We’ve often worked like that before, it’s really special. [for All You Need Is Me, for instance, a documentary about the Dutch artist Aad Donker, who committed suicide when he was still young, GH].

“I used to accept everything offered. Simple, I needed the work. When I was older, I had more choice and I hope that I will still have the opportunity to shoot good films. My choice now is based on whether I think a script is good. I’ve been a teacher at the film school in Łódź for five years now and since I started, I feel like a beginner again. It’s been a complete reset. The fact that I meet and supervise students from all sorts of countries for a few days every month, gives me so much energy.

As well as Zelazny most, in the last few years, I’ve shot another feature film in Poland Safe Inside (Renata Gabryjelska, 2019, still to be released) as well as an episode for the television series Van der Valk (English detective series set in Amsterdam) and, as well as that, I’ve worked for a big series in Poland, The House Under Two Eagles (Waldemar Krzystek), 100 shooting days, all forty-year-olds, young people. They wanted to work with me based on what I’ve done.”

RESET

So that reset then. A rejuvenation treatment precisely when Kukla feels a little ignored in the Netherlands. The man who is so well known for the major films, but is just as happy working on documentaries, although that has mainly to do with his collaboration with Van der Aar. “I can discuss things easily with him, we like to work together and we also plan so that we can do that.”

That brings the conversation back to those ‘long-term’ professional relationships, with Pieter Kramer, for instance. Kukla is one of those DoPs who thinks that it is so obvious how he works that he forgets to explain it. We are half way through the interview before he realises that the way he uses colour in his work may be of interest to others. He prefers to talk about the people he has worked with, and he keeps mentioning film titles. What is important for Kukla is that Kramer deals with people so well, that he knows how to create one big family. That he is appreciated. Filming seems to be just something that happens by itself, ‘just storyboard everything’, as if that’s nothing.

He wants to explain why he never wanted to go to the United States. “There are productions where it’s war every day. And I’d have to emigrate again. I’ve never wanted to do that and it’s an even worse country. I can still just ring someone up personally here, but that’s so hard in the US. And if the film flops, I get the blame. No, that’s not for me.

I was supposed to shoot an American film in Europe, because it’s cheaper here. That’s the only time I came anywhere near Hollywood.” Kukla talks about innumerable films for the whole of the interview, but often forgets to mention the title. He does that deliberately sometimes, he doesn’t want to be indiscrete about a particular director. However, he can cite the title in this instance. He even starts to laugh before he has uttered it: Deuce Bigelow: European Gigolo (Mike Bigelow, 2005, with the actor Jeroen Krabbé). The film had to be shot in Amsterdam.

“I’d had a conference call. They said that they didn’t like my showreel. I’d never shot comedy before, of course, but I’d already had a meeting with the director and one of the producers. They had hired me. We were going to drink a glass of champagne together. But in that conference call they asked me if I was married, if I was maybe homosexual, ridiculous things. I was so angry that I wanted to resign, but that wasn’t necessary in the end, because they’d already sacked me, luckily. It was such a big production, I’d anticipated all sorts of problems.”

When asked why he wanted to do it in the first place, Kukla answers both clearly and mysteriously at the same time: “You never know.”

On to the next story: The Zookeeper (Ralph Ziman, 2001), in which a well-known actor was meant to play the leading role. During a civil war somewhere in an unspecified East European country, a disillusioned ex-communist stays behind to look after the animals in the capital’s zoo until the UN arrives.

“It was the first major film that I did abroad. We were shooting in Prague, Czech Republic. This leading actor is notorious, he storms off the set, that sort of thing. We had a lot of time to prepare, three months. There was as much time as I wanted for the sets, for my storyboarding, to know precisely how I should film. Every Monday, a big Mercedes drove to Vienna to pick him up so that we could rehearse. Not once was he in it. On the first shooting day, 31st January 2009, he arrived hours late and it was already in the afternoon. He was a bit sloshed. He had four shooting days in his contract. He had to hit a young actor, a child actually, in a certain scene, and he hit him for real. He was terrible to work with. He left on the fourth day. The next day, I worked with a stand-in, a man who looked like him, to gain some time, but the actor never came back. The second choice was Sam Neil. We asked him on the Friday, and he was there on the Monday. We had to shoot everything again, which made everything at least 500 thousand dollars more expensive. The actor is still in one shot though,” laughs Kukla, “a bit of his finger.”

The Zookeeper finally premiered on 13th September 2001 at the film festival in Toronto, two days after 9/11. Nobody came. The film was a flop. That was terrible for Ziman, the director, for his career.”

NEW DEAL

In each interview with an NSC DoP, the New Deal is discussed, the pamphlet published in 2018. What does Kukla think about it? He must be able to agree with it? It is precisely the big productions that the pamphlet seems to address. However, Kukla doesn’t want to talk about the triangle of subsidizer, maker and producer. He isn’t interested in talking about the video village either. “Sombogaart,” he says, “always had an extensive video village and I had no objection to that. He often stood close to the camera, that’s what’s important.

What I find terrible in the Netherlands is that no money is put aside for promotion. That irritates me. I noticed that with Twin Sisters, for example.” Again, Kukla almost forgets to explain what he means. When asked, he says that he thinks that it is strange that a film manages to get made, but that no one seems to think about the fact the film then has to be ‘sold’, not just to an audience, but to other countries as well.

Speaking of money, budgets are always tight in the Netherlands. “When I was shooting Safe Inside in Poland, someone asked me where the second camera on my list was, when I just wanted to work with one. That was because I thought that it would be too expensive, but a second camera could easily be added, no problem. That way of thinking isn’t cheap, but it does benefit the film in the end.”

Finally, indirectly returning to the pamphlet, it depends, according to Kukla, on the director what sort of equipment is used on the set. “You have to discuss it with him. You have to tell him what you need. And, for example, I wouldn’t order a whole lorry full of equipment if I have to film on three locations in one day. I don’t have time for that, assembling and dismantling everything. It can’t be done. I make choices, how it can be done.

If you’re shooting with film, what I still do occasionally, you always have to work more precisely. You can’t just let the camera run all the time. So you prepare that well. You decide your ratio. Kukla gives an example of a film he prefers not to name, “I’d set the ratio at 12. It would make the budget € 3000 more expensive, but that’s nothing. But the director wouldn’t do it. Shooting a scene a maximum of 12 times was too risky for him, but that’s only if an actor doesn’t know his lines, otherwise there is no risk at all. For Zelazny most, I filmed a lot of the scenes in a maximum of two of three shots [with Alexa Digital, GH]. I never need many takes.”

Again, that preparation, and that is precisely what is underestimated in the Netherlands, Kukla reiterates. It is also exactly what the NSC New Deal is championing. “You would never be hired in America if that wasn’t arranged properly, because they know that it saves money. To go back to the pamphlet, I definitely agree that you can see from the majority of Dutch films that they are not quite complete, that there wasn’t enough preparation.

The budget is often inadequate, the screenplay isn’t ready. It is easy to explain why. There is little love for cinema here, definitely not amongst producers. If there’s no more money, there’s no more money, and there’s no one looking for a little bit more to shoot those few extra metres to make the film better. Even for post-production, there’s less time than before. Now we have seven days to do it, for the colour correction, etc. That really isn’t enough.”

THE STORM AND DE BENDE VAN OSS

Kukla is very enthusiastic about a number of productions. The Storm, for example, again with Sombogaart, about the Watersnoodramp, the North Sea flood of1953. “I’ve been very lucky with the films that I have shot so far. De Storm, so big, that is impressive, an experience like that. A whole swathe of land, somewhere in Belgium, near Antwerp, was flooded, specially for the film. They asked me when I arrived on set, ‘Piotr, where do you think the dyke has to go?’ The whole set was up to me. It took a while to build it, and the land was under two and a half metres of water in less than 48 hours.

We went there every day in little boats in the dark, just filming. We shot the rest of the film in the Netherlands, in December. What a production! I’m still very happy with it. The budget was also good and consequently, the production value. I love simplicity, less is more, and that worked well here. In terms of lighting, for instance. I don’t have to have hundreds of lamps on the set.”

At the same time, everything doesn’t just have to be functional all the time for Kukla. He explains what he means using an example, “I am a real fan of Hitchcock’s and Polanski’s films. I understand it. That language of film. It has to be right. And their films are right.”

After I say that he has to explain, he says, “In Chinatown, he [Kukla means Jack Nicholson’s character] walks towards a house. The camera goes with him, you see it through his eyes, there is no overview. Polanski filmed it like that to make it exciting, you don’t exactly know where you are, what you’re going to see. So fantastically, so consistently, so simply filmed. Those are things with regard to the language of film that I remember. I can use that, I have a whole library in my head now.”

De bende van Oss, the crime drama about a period in the thirties in the town of Oss and a maffia-like group of criminals, is another film Kukla could talk about for a long time. That has to do with the respect he has for director André van Duren and because “he is different, funny and so passionate. He has an open vision. And he also loves storyboarding. André is also very good with actors.”

Although Kukla hopes to make many more films with him, Van Duren is currently filming with a different DoP. A woman, for diversity. “We should really stop doing that. I also lost a job in Poland at the start of the year for the same reason.”

Talking about De Bende van Oss also leads Kukla to Silvia Hoeks. “She is fantastic. I also thought she was great in The Storm. I was crazy about how she works.

At a given moment, she had to drown. It was so cold, it was autumn. She had a wet suit on, of course. Everyone did. The crew on the floating second camera unit were freezing. But in the evening she still wasn’t satisfied and wanted to do it again. I thought that that was amazing. It wasn’t necessary, because the scene was good, luckily, but that perfectionism, I love that. And that’s how you make a good team together.

I always use the film in Poland at the film school to show how you can combine studio and location work well. A lot of scenes, in the cafe, for example, were shot in the studio, but it is difficult to make that look authentic, but it worked very well, in my opinion. I filmed on location in a little street and used the entrance to the cafe, but the interiors were all shot in the studio. Mimicking that and lighting it believably is quite a job. That’s really the hardest part. You see that straight away in a lot of films.

The film opened in Utrecht at the Netherlands Film Festival [2011, GH]. I really thought that we would win more prizes with it, but the calf [the Golden Calf, the festival award, GH.] we won was just for the music [Het paleis van boem, GH]. I was nominated though, André was as well for the screenplay, but Silvia should have at least been nominated. I once won the Silver Frog at Camerimages in Poland for Twin Sisters for which I was also nominated in Utrecht. And the crazy thing is, after the nomination, nobody rang me for seven months. People think that you’ve become too expensive, or too busy. But I had nothing to do!

I’m not interested in prizes any more now, it doesn’t bother me now, not winning. I’m completely cured. I’ve been on too many juries now and seen how it works. It has to do with personal taste, of course, but also how films are programmed for the jury. We watch three films per day from Monday to Friday. You remember the films on the first and last day best. The films that are programmed in between, perhaps deliberately by the organisation, have less chance.

So, prizes mean nothing to me, but they certainly did once.”

Kukla doesn’t really know what he most likes to shoot now, but what he does know, is that he loves major productions now and then, with a hundred or more extras, that sort of work. “Wonderful”, he says, “but I always want to operate the camera myself. If directors only want me to be the DoP, the manager, then I don’t like that very much. I want to hold it myself, because even when shooting big scenes, I can do the filming myself just fine. I’m extremely well prepared anyway, I have storyboarded everything, I know each movement by heart. I have an overview and a plan A, B and C. That’s why I can adapt quickly, you have to. I always have alternative plans ready.”

COLOUR AND LIGHT

How does Kukla regard his oeuvre, now that he has been going for so many years? He doesn’t want to think about it. “What do you mean? This isn’t over for me yet, not by a long chalk. I feel like a beginner. I might have something to say about it in 20 years, but not yet. I work now with so many young people. That’s inspiring, I learn so much, I’m still changing. And André [van Duren, GH] or Wim [van der Aar, GH] always surprise me. It’ll stay like that.

After some insistence about his oeuvre, it seems like Kukla suddenly realises it: the colours, the light. That is something that all his films have in common perhaps. But what precisely?

“When I’m thinking about colour, I always ask myself, what do I want to use? How do I light what I want to say? That. Cinema is so excessive these days, everything is too much. Every second shot has to be filmed with drones, for instance, that kind of work. I’m not really into being trendy; it has to be in service of the film. I’m happy to film unusual shots, but they have to fit.”

He refers to painting and finally gives a concrete example after almost two hours of talking: Johannes Vermeer, seventeenth century Dutch paintings. Later, when Kukla is asked to check the text of the interview for any omissions, he writes that it might be a cliché to mentioning Vermeer, but it is also the truth. “Vermeer’s light, that fascinates me, “says Kukla. “Little saturation, everything a bit brown and also slightly cool. The scenes in the Second World War in Twin Sisters are even almost in black and white. He mentions DoP Vittorio Storaro (Apocalypse Now, The Sheltering Sky, etc.) and that he has written books about the meaning of colour in film. “I wouldn’t go as far as that, but it is interesting. I’m more of the opinion that each script has a different colour. I always tell my students about the colour approach. I once worked with a colleague who, per scene, always put colours in the scripts with a felt-tip pen. That was so clear, you just see it straight away.

At the end, Kukla talks about a subject again that he brought up himself: that he is noticing that he sometimes isn’t asked for films any more by a director who he used to work with for years. He is not sure why either. “I am definitely suffering from the fact that the white man of a certain age is not in a good position at the moment. Then I do just go back to Poland, but I also really like working here.”

He emphasizes that he does understand if someone works with a different DoP once in a while. He might even recommend it. But he would like to know why a number of good collaborations seem to be coming to an end after several years. He is convinced that producers are doing that because of his age, and that saddens him. “I thought I was finished five years ago, because of that, but then I received a request from Poland, and then a second and a third and it looks like it’s not over yet.”

Text: Gerlinda Heywegen

Translation: Terry Ezra